Mats Wienerholm remembers Porgy Salming

Porgy Salming is gone.

I write away, because it will never die.

He leaves behind so many memories, so many friends, so much love and so many wonderful moments that he will live forever.

Few are blessed to make such an impression in one lifetime.

You have influenced and touched many.

Not just for his self-sacrificing way of playing hockey, never giving up, always sacrificing mercilessly for his teams, and never backing down on anyone.

But also throughout his life story, starting from his difficult upbringing in Kiruna, his father’s early death in a mining accident when he was five years old and his openness, strength and honesty to the very end.

Like when he arrived in Toronto to be honored for the last time and only a few days later found himself at the Hockey Gala.

It was his way of saying goodbye to the audience he’s always loved.

Everyone understood that there was not much time left. Not least Börje.

But he went straight to the heart.

The last time.

And now, after just over a week of heartbreaking scenes, he’s gone.

My last encounter with Börje was during the summer EC at the Munich Athletics in mid-August.

He was there to watch his daughter Bianca attempt a new personal record and place high in the heptathlon and sat among friends and family as if nothing had happened.

At that time, he had just been told that he was suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and asked to be left in peace after the disease was made public. I respected that, but I couldn’t avoid giving a salute when we ran into each other behind the stands.

He smiled and looked as usual.

but he could scarcely utter any words, when he tried to explain that the disease had lodged in his throat, and that his voice could no longer bear.

He faced an opponent that could not be defeated.

It was already a sensation in the early years

The guy who defeated everything and everyone, he didn’t even get a fair shot this time around.

The most terrible disease that has no cure and which hides behind an unknown combination of letters ALS – amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

I don’t even know where to start, when I look back on all the great moments I had with Porgy.

I saw him play live during his early start at Brynäs in the early years of the 1970s. It was a sensation even then.

Then there was a long break before I saw him live again.

It was in the away game against the New York Rangers in 1989.

I had been to Alpine WC in Vail Colorado and on the way home we stopped to follow then National Team Captain Tommy Sandlin’s search for NHL players before the WC home in the newly built Globen.

Sandlin wasn’t there to watch 37-year-old Salming first-hand, but I watched his smile widen and wide as I sat next to him in the stands at Madison Square Garden.

In the end, it reminded me of the people from Madrid in the Disney Christmas classic Ferdinand the Bull.

– We must get it!

He was in a situation where no one expected Salming to age in the WC lineup, but the singles match was enough to convince Sandlin.

At the time, Börje had not played a WC tournament in sixteen years.

He was almost forgotten by the younger generations in Sweden and in the second of his total of sixteen seasons in the NHL.

But that WC Championship in the Globe and his last two seasons in the AIK and SHL made him a household name again. They brought back all the memories.

All the old stories re-told and he regained the place he deserved here at home.

In Toronto, he was already a legend and has long been a statue outside the Air Canada Center.

Nobody forgets there.

History wrote when he took the lead

For Börje Salming, history was written when he broke through and became the first major star to make the step from Europe to the NHL.

It has become a symbol that even a player from across the Atlantic can survive in hockey’s most brutal world, as every Canadian on the opposing team has done everything to make you give up, pack up and head home to safety.

They didn’t want to see any European stealing jobs.

And there are absolutely no “Swedish chickens,” cowardly Swedes, as they called the yellow-clothed Tre Kronor after the practice game in Hovet in 1972, when the NHL players stopped in Stockholm on their way to the second half of the historic Challenge Series against the then Soviet Union.

Porgy Salming was almost single-handedly changing that.

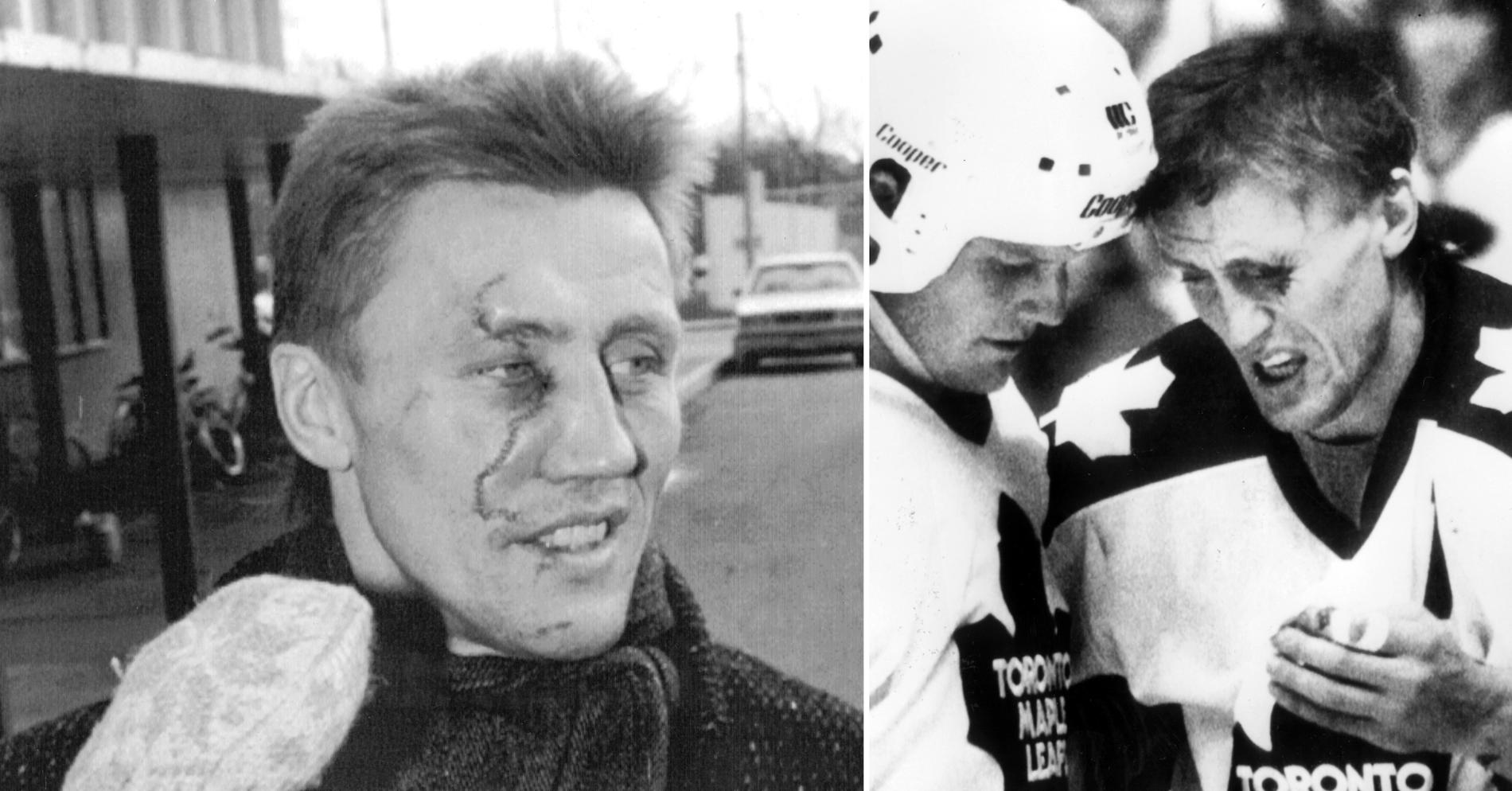

Back in the 1970s, the NHL was a brawler-filled league where entire teams could throw up the gloves in a “bench brawl” back then, when both teams left the bench and everyone was fighting everyone.

There was nowhere to flee. There was never going back

When Börje Salming threw down the gloves before his first fight in the NHL, he didn’t even know who he was up against.

Some might call it luck, as one of the worst rawhide in the NHL stood with a toothless grin and fists raised in front of him.

Philadelphia Dave Schultz.

hammer.

hammer.

But even if Porgy knew, I don’t think he would have cared.

He told me later that he hadn’t thrown a single punch at me.

– I had to learn how to hold the shirt so that he wouldn’t get any blows. And I held on until my fingers showed up.

Afraid?

no never.

He never bowed

Despite the constant assaults, stabbings and punches in the league where none of the existing rule books were enforced. Pouret described it by saying that what results today from a ten-match suspension barely led to a runner-up.

His body was sometimes so bruised that he did not dare to look in the mirror.

But he never bowed.

If he gets a piece of pork, he chops it up.

If someone throws the glove away, they throw it away.

It’s not a moralizing story for hockey guys today, but at the time it was respected and admired by teammates, opponents, and fans alike.

This Swede cannot be broken.

It was made of the same hardwood as the windswept mountain birch of Kiruna during its upbringing. He had a pain threshold up to Kebnekaise.

At the same time, he was ruthless with himself when laying directly on the ice and covering shots in his own territory, while also being a constant offensive threat.

The crowd in Toronto has never seen anyone sacrifice so completely for the team.

It was love at first sight.

He had a +38 plus/minus his first season with the Maple Leafs in 1973-74. He was by far the best on the team.

And with every shot he took, every shot he covered, the fans’ love grew.

This accounts for what most people view as the greatest moments of his career.

As documented via faded TV images from the 1976 Canada Cup,

Tre Kronor will take on the USA in the opener at the classic Maple Leafs Garden and when Salming was introduced the entire arena rose and gave him a standing ovation.

She never wanted it to end, but eventually did because there was a game to play.

Nobody remembers her today.

It was a pioneering era

In the stands, some Canadians drew a banner with the text:

“#5 in Sweden, #21 in Toronto, #1 in the world”.

This is how great a Swede from Kiruna is in the home of hockey, the largest city in Canada.

It takes something extra to get this status in a country that can stack stars on top of each other.

But when Borghi and Inge Hammarstrom came to Toronto, they pioneered as players who had grown up in Europe in a league where only defenseman Thomy Bergmann had ever filled a regular spot on the NHL team. And that late in the previous season.

There were neither Finns, nor Russians, nor Czechs.

It was a pioneering era that opened the door for all the Europeans who came after.

Of course, there are plenty of stories about the love Toronto fans have for their back-to-back Swedish champions.

Most notable is when he was hit in the eye in a game against the New York Islanders in 1978.

It was hanging from the eye socket.

Börje was at risk of going blind and was lying awaiting a response after an emergency operation.

Then many fans offered to donate one of their healthy eyes to the Swede.

That’s how far they were ready to go to prolong the march of their beloved back.

Now it was happily over, the operation was a success and Purée left the hospital with no hands and managed to take a bag full of fan mail and lucky cards collected out the door.

And love never rusts in a city whose ancient heroes never forget.

I followed Börje several times there in Toronto in 2000, when he returned to be greeted by the crowd of the day and hoisted his jersey to the roof of the new Air Canada Center in 2006.

But it is almost impossible to express its magnitude in the birthplace of hockey.

It’s like you’ve been there and seen it with your own eyes.

He knew respect and reverence for everyone he met.

When before I put on the shirt I was getting up and walking with the swinging Börje along a city street, a fire engine came speeding in one direction and I wondered where there was a fire somewhere.

But it stopped with wheels screeching in front of us, four firefighters jumped up and ran to Porgy.

They just wanted to say hello, ask for an autograph and honor their childhood hero.

At an intersection, a bus swerved and stopped traffic, while the driver ran with a ticket booklet in his fist.

Not to sell tickets, but because it was the only piece of paper he had to write Salming’s signature on.

The overwhelming attention might be stressful for many, but Börje always stopped by, and always had time to exchange a few words. always smiling.

This humility followed him throughout his life.

He remained the same humble spirit that old Brinass leader Thor Wakeberg recruited from Kiruna, with the promise of a club jacket and a pair of expendable shoes.

Despite all the success and all the fame.

It was also part of his greatness.

Börje Salming wasn’t named the best defenseman in the NHL, but he was close at a time when European players were something completely new to the league and the jury was exclusively North American. He finished second in Norris Trophy voting twice and third on two other occasions in the 1970s. That’s just it, accomplished in silence.

He was the first person from outside North America to be nominated.

Same with the Calder Cup as Rookie of the Year. In his debut season in 1973-74, he finished third in that poll, won by Denis Potvin of the New York Islanders.

It took until 2001 before a defender from Europe regained the Norris Cup, and then it was another Swede who broke this pattern – his friend Niklas Lidström.

But it didn’t seem to matter what awards he got without it.

But the biggest prize was the love and respect he created.

at everyone.

I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone say a bad word about Börje Salming.

There is nothing greater than that.