Norland window closes.

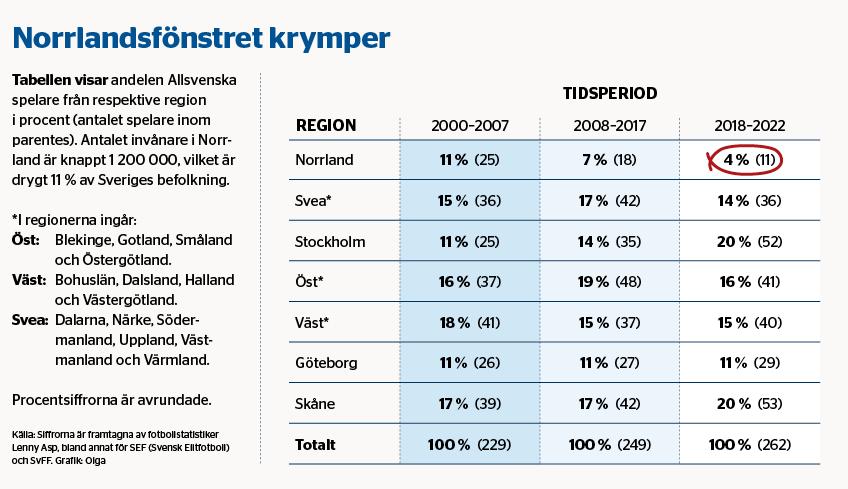

A survey from SvFF showed that the percentage of Allsvenskan players from Norrland decreased from eleven to four percent during the 2000s.

“South Sweden runs the X2000 and we’re still on the podium,” says Michael Floron, head of office at Norrbottens FF.

On the surface, the nine Norrland counties cover 60 percent of Sweden. But whoever settles into the stands for a Swedish men’s match does not expect to see players from the northern region.

When the Swedish Football Association determines where the men’s players come from in our top division, it is not surprising that the majority have been born in southern Gävle. Without the steep Norland curve.

Until 2007, every ninth Allsvenskan player came from Norrland, which was proportional to the population. Just over a decade later, the figure had shrunk by about two-thirds, to just four percent (or eleven players). This is despite the fact that Östersund and Gif Sundsvall were in Allsvenskan during this period.

The balls become square.

Michael Floron is the head of the office at Norrbottens FF and sighs at the assembly.

– Four percent? There is surprisingly little. But it reflects society and football from an international perspective. The competition has become very tough and the training opportunities here are even worse. I still think we should produce more, maybe not for the national team but for the Allsvenskan, he says.

What does it matter if half of Sweden is not better represented in the men’s league?

In all sports, it’s good to set an example. We have kids and young adults dreaming of becoming professional footballers, but with those numbers behind us, we find it difficult to point to any role models from here. It is up to us as leaders to keep the flame burning, to try to reverse the trend.

So what does it all boil down to? Floron points to a combination of a lack of plans and that the pattern of coaching changed in the 2000s. Previously, football was played from March to October and switched to indoor sessions every now and then during the winter. Nowadays, everyone who can also work hard during the cold months.

But in Norland there are no halls. The only two full-size teams are in Lulea and Betio, the other teams have to compete with, among others, floorball and handball for regular indoor times.

– You can also practice outdoors on artificial turf. But doing it when the temperature drops to minus 25 degrees doesn’t provide any extra quality. It doesn’t matter if the court is hot when the balls get square from the cold, Floron says.

Big difference for Norway

In compiling the association, Sweden has been compared to Norway.

We have 15 full-size indoor halls with artificial turf, while our neighboring country – although half as populous – has 35. And where in Sweden there are 83 heated, full-size outdoor artificial turf courts, there are nearly 180 in Norway.

One explanation for this difference could be the funding model, since it is the municipalities or associations themselves who build their halls in Sweden with the help of contributions from various funds. In Norway, the cost is shared between the state, the municipality and the club.

The consequence? Perhaps it is no coincidence that the proportion of Allsvenskan players from Stockholm has doubled since 2007. And that the most successful Norwegian club in recent times is Bodö / Glimt, which is at the same latitude as Gällivare, while Allsvenskan 2023 is completely devoid of Northern teams.

– It’s crowded in northern Norway and we’ll need halls in all our municipalities. Not full size everywhere, but 70 x 40m is sufficient. But there is simply a different view in Norway, where they care more about the countryside and smaller municipalities, says Michael Floron.

Footnote: Women’s league statistics are missing.